Although almost on my doorstep, I have to admit it was years before I discovered the magnificent carved stones housed in Govan Old Parish Church. Hundreds of years of history, belief and kingship set in stone and preserved for all to see in the heart of Glasgow. The Govan Stones are an exceptional array of early medieval Christian sculpture that show clearly the importance of this place to the Kings of Strathclyde.

Although almost on my doorstep, I have to admit it was years before I discovered the magnificent carved stones housed in Govan Old Parish Church. Hundreds of years of history, belief and kingship set in stone and preserved for all to see in the heart of Glasgow. The Govan Stones are an exceptional array of early medieval Christian sculpture that show clearly the importance of this place to the Kings of Strathclyde.

According to tradition, the original church on this special site was founded early in the 6th century and dedicated to St Constantine. Built of wood and close to a holy well (a location much favoured by the Celts) it was surrounded by an almost circular wall.

The people who lived here at that time were neither Scots nor Picts, rather Old-Welsh-speaking Britons, part of a powerful kingdom ruled from Alt Clut – Dumbarton Rock. But then came the dreaded Vikings who sailed up the Clyde and in 870 AD the mighty fortress of Dumbarton fell to those ferocious Norse warriors.

One of the hogback Viking Stones

However, Dumbarton’s loss was Govan’s gain as it was to Govan that the new kings of Strathclyde looked to establish their power base. Already an important religious site, Govan now grew as a political and administrative centre: the Christian and the secular powers in the kingdom very closely intertwined. A growing sign of that increased status and subsequent wealth is reflected in what became known as ‘The Govan School’ of carving, which flourished between 900 and 1100 AD. Swirling snakes, elaborate interwoven decoration, mounted warriors, biblical scenes, huntsmen and saints – it’s all there!

As are five massive Viking hogback grave markers, which are truly monumental! At first glance they look like huge humpbacked beasts, but on closer inspection you can see that some are carved to represent wooden-tiled roofs; copies, possibly, of the wooden houses of important Viking chiefs of settlements or bases further west, who recognised the immense spiritual prestige of St Constantine’s Church at Govan and who craved the recognition burial at such an important Christian site would give them.

As are five massive Viking hogback grave markers, which are truly monumental! At first glance they look like huge humpbacked beasts, but on closer inspection you can see that some are carved to represent wooden-tiled roofs; copies, possibly, of the wooden houses of important Viking chiefs of settlements or bases further west, who recognised the immense spiritual prestige of St Constantine’s Church at Govan and who craved the recognition burial at such an important Christian site would give them.

The Tall Ship reflected in the dramatic windows of the Riverside Museum

Not far from the Govan Stones you’ll find Fairfield Heritage Centre which tells the story of Govan’s long shipbuilding tradition. It also tells the story of brave and determined women like Mary Barbour, a leader in the Rent Strikes of 1915, when, during the First World War, the women of Govan courageously stood against corrupt landlords.

Cross the mighty River Clyde over the brand new pedestrian bridge linking Govan and Partick, and you reach the Riverside Museum, with the Tall Ship berthed in front of it. Along this short stretch of the river there’s much to see and discover. Govan and the Clyde have a long and fascinating history – some good, some not. But all part of the past that has led to the Govan of today where change is afoot. Govan’s story is not done yet!

The full article can be found in issue 98 of iScot magazine, available through Pocketmags.

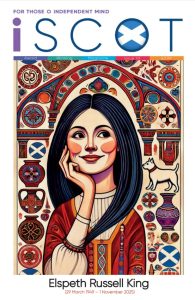

In May 2018 I had the privilege of interviewing Dr Elspeth King, not long before her retirement from the Stirling Smith Museum. She had so much to say that the article ran to nine pages in the May 2018 edition of iScot Magazine!

In May 2018 I had the privilege of interviewing Dr Elspeth King, not long before her retirement from the Stirling Smith Museum. She had so much to say that the article ran to nine pages in the May 2018 edition of iScot Magazine!

Have you ever found yourself walking through a supermarket and suddenly realised that you’re humming along to the music playing quietly in the background? Music that’s familiar, even if, like many of us, you can’t remember the words after the first couple of lines!

Have you ever found yourself walking through a supermarket and suddenly realised that you’re humming along to the music playing quietly in the background? Music that’s familiar, even if, like many of us, you can’t remember the words after the first couple of lines!

Is it possible that classic American Gothic Horror got off the ground thanks to a small town in Ayrshire? That idea might not be as far-fetched as you think! For none other than Edgar Allan Poe spent time as a young boy in his foster parents home town of Irvine. And according to a popular local tradition he improved his reading by tracing out the names on gravestones in the parish churchyard!

Is it possible that classic American Gothic Horror got off the ground thanks to a small town in Ayrshire? That idea might not be as far-fetched as you think! For none other than Edgar Allan Poe spent time as a young boy in his foster parents home town of Irvine. And according to a popular local tradition he improved his reading by tracing out the names on gravestones in the parish churchyard!

Scottish artist Margot Sandeman (1922-2009) had a long-standing connection with the Isle of Arran. There were many happy childhood holidays with her family on the island. Later came sketching and painting trips with her good friend and fellow Glasgow School of Art student Joan Eardley. Finally, in 1973 Margot and her husband bought one of the little cottages up in High Corrie.

Scottish artist Margot Sandeman (1922-2009) had a long-standing connection with the Isle of Arran. There were many happy childhood holidays with her family on the island. Later came sketching and painting trips with her good friend and fellow Glasgow School of Art student Joan Eardley. Finally, in 1973 Margot and her husband bought one of the little cottages up in High Corrie. In the little exhibition, No More Sheep, currently on in Kelvingrove Art Gallery in Glasgow, a selection of Margot Sandeman’s delicate paintings mourns the passing of a way of life she’d witnessed throughout the long years she’d been coming to Arran. In the early days sheep had played a big part in the life of the islanders and were seen all over the island. By the late 20th century that way of life was passing, if not gone altogether. And through these pictures she mourns that passing.

In the little exhibition, No More Sheep, currently on in Kelvingrove Art Gallery in Glasgow, a selection of Margot Sandeman’s delicate paintings mourns the passing of a way of life she’d witnessed throughout the long years she’d been coming to Arran. In the early days sheep had played a big part in the life of the islanders and were seen all over the island. By the late 20th century that way of life was passing, if not gone altogether. And through these pictures she mourns that passing. He was a scientist who helped put the first men on the moon. While his interest in the paranormal earned him the nickname of Glasgow’s Ghostbuster. And his thrillers, many set on Scottish islands, were for decades amongst the most sought-after books in public libraries. Yet, surprisingly, he’s little-known today.

He was a scientist who helped put the first men on the moon. While his interest in the paranormal earned him the nickname of Glasgow’s Ghostbuster. And his thrillers, many set on Scottish islands, were for decades amongst the most sought-after books in public libraries. Yet, surprisingly, he’s little-known today. In his thrillers, he wrote about places he knew well, in particular the islands of Arran, St Kilda and Mull. Fast-paced, some of his novels come with elements of science-fiction based on his own scientific experience and knowledge. In others, he looks at that great question of ‘what if’ specific events in history had taken a different course and left us with a very different present.

In his thrillers, he wrote about places he knew well, in particular the islands of Arran, St Kilda and Mull. Fast-paced, some of his novels come with elements of science-fiction based on his own scientific experience and knowledge. In others, he looks at that great question of ‘what if’ specific events in history had taken a different course and left us with a very different present. In this article, in the 100th issue of

In this article, in the 100th issue of

Is it incompetence, neglect or sheer stupidity that stops our government dealing quickly and efficiently with essential matters of infrastructure? Matters that are vital for the sustainability of our rural communities.

Is it incompetence, neglect or sheer stupidity that stops our government dealing quickly and efficiently with essential matters of infrastructure? Matters that are vital for the sustainability of our rural communities. Although almost on my doorstep, I have to admit it was years before I discovered the magnificent carved stones housed in Govan Old Parish Church. Hundreds of years of history, belief and kingship set in stone and preserved for all to see in the heart of Glasgow. The Govan Stones are an exceptional array of early medieval Christian sculpture that show clearly the importance of this place to the Kings of Strathclyde.

Although almost on my doorstep, I have to admit it was years before I discovered the magnificent carved stones housed in Govan Old Parish Church. Hundreds of years of history, belief and kingship set in stone and preserved for all to see in the heart of Glasgow. The Govan Stones are an exceptional array of early medieval Christian sculpture that show clearly the importance of this place to the Kings of Strathclyde.

As are five massive Viking hogback grave markers, which are truly monumental! At first glance they look like huge humpbacked beasts, but on closer inspection you can see that some are carved to represent wooden-tiled roofs; copies, possibly, of the wooden houses of important Viking chiefs of settlements or bases further west, who recognised the immense spiritual prestige of St Constantine’s Church at Govan and who craved the recognition burial at such an important Christian site would give them.

As are five massive Viking hogback grave markers, which are truly monumental! At first glance they look like huge humpbacked beasts, but on closer inspection you can see that some are carved to represent wooden-tiled roofs; copies, possibly, of the wooden houses of important Viking chiefs of settlements or bases further west, who recognised the immense spiritual prestige of St Constantine’s Church at Govan and who craved the recognition burial at such an important Christian site would give them.

A question: What do William Shakespeare, Jules Verne, Agatha Christie, Peter May and Enid Blyton all have in common? And the answer? They’ve all used islands as settings for some of their most exciting and memorable works.

A question: What do William Shakespeare, Jules Verne, Agatha Christie, Peter May and Enid Blyton all have in common? And the answer? They’ve all used islands as settings for some of their most exciting and memorable works. ‘Climb every mountain …’

‘Climb every mountain …’  Whose blood flows through your veins? Are you descended from dark-haired Celts, or fair-haired Norse Vikings. Or even those unfortunate Spanish sailors whose ships floundered in the stormy waters off the Scottish coasts in the aftermath of the Spanish Armada of 1588 and stayed on (think of Jimmy Perez!).

Whose blood flows through your veins? Are you descended from dark-haired Celts, or fair-haired Norse Vikings. Or even those unfortunate Spanish sailors whose ships floundered in the stormy waters off the Scottish coasts in the aftermath of the Spanish Armada of 1588 and stayed on (think of Jimmy Perez!).

And it’s a place to explore and spend time on. To stop for a while and ponder on the lives of those men and women who chose to live here in the past. And perhaps even to wonder what they would make of our lives today? Of our priorities and beliefs? Of our feelings and actions towards our fellows? What would they think of us, I wonder? Now that would be interesting!

And it’s a place to explore and spend time on. To stop for a while and ponder on the lives of those men and women who chose to live here in the past. And perhaps even to wonder what they would make of our lives today? Of our priorities and beliefs? Of our feelings and actions towards our fellows? What would they think of us, I wonder? Now that would be interesting!