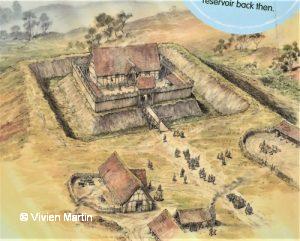

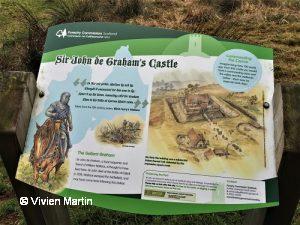

The view might be very different from John de Graham’s time, but the setting is still as commanding. De Graham, friend and ally of William Wallace, is believed to have had his home on this spot, overlooking the Carron Valley in Stirlingshire. There’s a picture on the information board showing what the ‘castle’ would have looked like: a medieval earthwork with a substantial timber-framed hall, defended by an impressive square moat. The line of the moat is still very much in evidence, though nothing remains of the hall, and today the mighty Carron Reservoir fills much of the valley below.

The view might be very different from John de Graham’s time, but the setting is still as commanding. De Graham, friend and ally of William Wallace, is believed to have had his home on this spot, overlooking the Carron Valley in Stirlingshire. There’s a picture on the information board showing what the ‘castle’ would have looked like: a medieval earthwork with a substantial timber-framed hall, defended by an impressive square moat. The line of the moat is still very much in evidence, though nothing remains of the hall, and today the mighty Carron Reservoir fills much of the valley below.

John de Graham of Dundaff (another name for this fortified site), was a 13th century Scottish noble who fought alongside Wallace in the First Scottish War of Independence, and who fell at the Battle of Falkirk on 22 July 1298. On that terrible day the Scots, unable to withstand the force of the heavy English armoured cavalry and the deadly Welsh longbows, were defeated by Edward I of England. De Graham died but Wallace survived and is said to have sought out de Graham’s body and carried it from the battlefield himself. De Graham was the most notable casualty of that terrrible day and is buried at Falkirk Old Parish Church. Wallace then retreated to de Graham’s home by the Carron Water.

John de Graham of Dundaff (another name for this fortified site), was a 13th century Scottish noble who fought alongside Wallace in the First Scottish War of Independence, and who fell at the Battle of Falkirk on 22 July 1298. On that terrible day the Scots, unable to withstand the force of the heavy English armoured cavalry and the deadly Welsh longbows, were defeated by Edward I of England. De Graham died but Wallace survived and is said to have sought out de Graham’s body and carried it from the battlefield himself. De Graham was the most notable casualty of that terrrible day and is buried at Falkirk Old Parish Church. Wallace then retreated to de Graham’s home by the Carron Water.

Many years later a famous narrative poem, The Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace (also known as The Wallace), was written by the poet Blind Harry. It portrays Sir John de Graham as one of William Wallace’s principal supporters and describes Wallace’s feelings of loss and sadness at the demise of his friend. There’s no doubt that de Graham’s death was a sore blow to Wallace, who lost not only his right-hand-man, but also a close friend.

Many years later a famous narrative poem, The Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace (also known as The Wallace), was written by the poet Blind Harry. It portrays Sir John de Graham as one of William Wallace’s principal supporters and describes Wallace’s feelings of loss and sadness at the demise of his friend. There’s no doubt that de Graham’s death was a sore blow to Wallace, who lost not only his right-hand-man, but also a close friend.

How certain can we be that this was John de Graham’s family home and that he was the man so close to Wallace? Matthew Ritchie, an archaeologist with the Forestry Commission Scotland who manage this site, writes, “A 13th century charter records ‘the whole waste lands of Dundaff and Strathcarron, which was the King’s forest’ being granted by Alexander II to John’s father, Sir David de Graham. That a John de Graham was the third son of Sir David de Graham is not in doubt – but was this the same John immortalised in The Wallace as having fallen at the Battle of Falkirk, or perhaps a son or relative?”

Ritchie continues, “Although Blind Harry’s poem was written long after the event, it does clearly link his Sir John de Graham to the area; and although the earthwork was likely built some years beforehand, it does mark the feudal estate of Dundaff, property of the de Graham family. Fact and fiction do seem to meet at Sir John de Graham’s castle to tell a story of place that is firmly rooted in the past.”

Ritchie continues, “Although Blind Harry’s poem was written long after the event, it does clearly link his Sir John de Graham to the area; and although the earthwork was likely built some years beforehand, it does mark the feudal estate of Dundaff, property of the de Graham family. Fact and fiction do seem to meet at Sir John de Graham’s castle to tell a story of place that is firmly rooted in the past.”

In the past spelling was not fixed or final and you’ll find that John de Graham’s name appears in different forms. In Blind Harry’s The Wallace his name is given as ‘Schir Jhone the Grayme’, while his tomb has him as Sir John the Grame. Then there’s the Society of John de Graeme, a group set up in 2016 to highlight the role of de Graham and Scottish history in general. But that’s not all. His name also survives in the Grahamston area of Falkirk – even in Falkirk Grahamston Station!

The Carron Valley

This site in the Carron Valley is an important part of Scotland’s story and heritage and as as such is a protected Scheduled Monument. We may never have known the man, but we can stand where both he and Wallace stood, and that’s a fine thing.

For those living in the Central Belt of Scotland the countryside is never far away. Despite being the area with the highest population density in Scotland (3.5 million out of 5.4 million), it doesn’t take long to reach the clean air and open spaces of the countryside.

For those living in the Central Belt of Scotland the countryside is never far away. Despite being the area with the highest population density in Scotland (3.5 million out of 5.4 million), it doesn’t take long to reach the clean air and open spaces of the countryside.

We all have different ways of dealing with life’s ups and downs. For me, the very best way of dealing with the effects of upsets and hurts, and for putting life back into perspective, is to take to the hills.

We all have different ways of dealing with life’s ups and downs. For me, the very best way of dealing with the effects of upsets and hurts, and for putting life back into perspective, is to take to the hills. And as you look across the wide expanse of countryside that surrounds you, the world takes on a whole new perspective. The view is magnificent. The air is fresher and cleaner: the encircling trees ‘breathing’ in our dirty air and ‘breathing’ out the clean oxygen that fills our hearts and lungs and makes us stand up straighter, bringing a new sense of calmness in its wake.

And as you look across the wide expanse of countryside that surrounds you, the world takes on a whole new perspective. The view is magnificent. The air is fresher and cleaner: the encircling trees ‘breathing’ in our dirty air and ‘breathing’ out the clean oxygen that fills our hearts and lungs and makes us stand up straighter, bringing a new sense of calmness in its wake. The trail to the waterfall is a delight. Running steeply downhill, it twists and turns, with strange sights awaiting! Turn one corner and there are the two young deer startled into motionlessness. Turn another and you come across the Magic Tree. Turn a third and you’re faced by the strange ghostly figures that stand so very still and silent among the trees – ethereal and alien looking, yet at the same time reflecting back strange visions of ourselves.

The trail to the waterfall is a delight. Running steeply downhill, it twists and turns, with strange sights awaiting! Turn one corner and there are the two young deer startled into motionlessness. Turn another and you come across the Magic Tree. Turn a third and you’re faced by the strange ghostly figures that stand so very still and silent among the trees – ethereal and alien looking, yet at the same time reflecting back strange visions of ourselves. Then, turn one further corner, and come face to face with a force of nature: the waterfall crashing and roaring through the gorge, thundering over rock and down the cliff face as the swollen burn races in torrents past your feet. After heavy rain the might of the water is unmistakable. Magnificent – and a little bit terrifying too!

Then, turn one further corner, and come face to face with a force of nature: the waterfall crashing and roaring through the gorge, thundering over rock and down the cliff face as the swollen burn races in torrents past your feet. After heavy rain the might of the water is unmistakable. Magnificent – and a little bit terrifying too!